-

- May 17, 2024

- 0

The Turn of the Month Effect

The turn of the month effect refers to the tendency for stock markets to experience significantly positive returns during the last few days of one month and the first few days of the next month. This was first identified by Lakonishok and Smidt (1988). (History books say Mount Kilimanjaro was “discovered” by the German missionary Johannes Rebman. This makes us wonder why the people who were living on the mountain hadn’t noticed it before. Similarly, the “discovery” of the turn of the month effect is probably an example of academic colonialism, and the effect was almost certainly known to some practitioners before their study was published.)

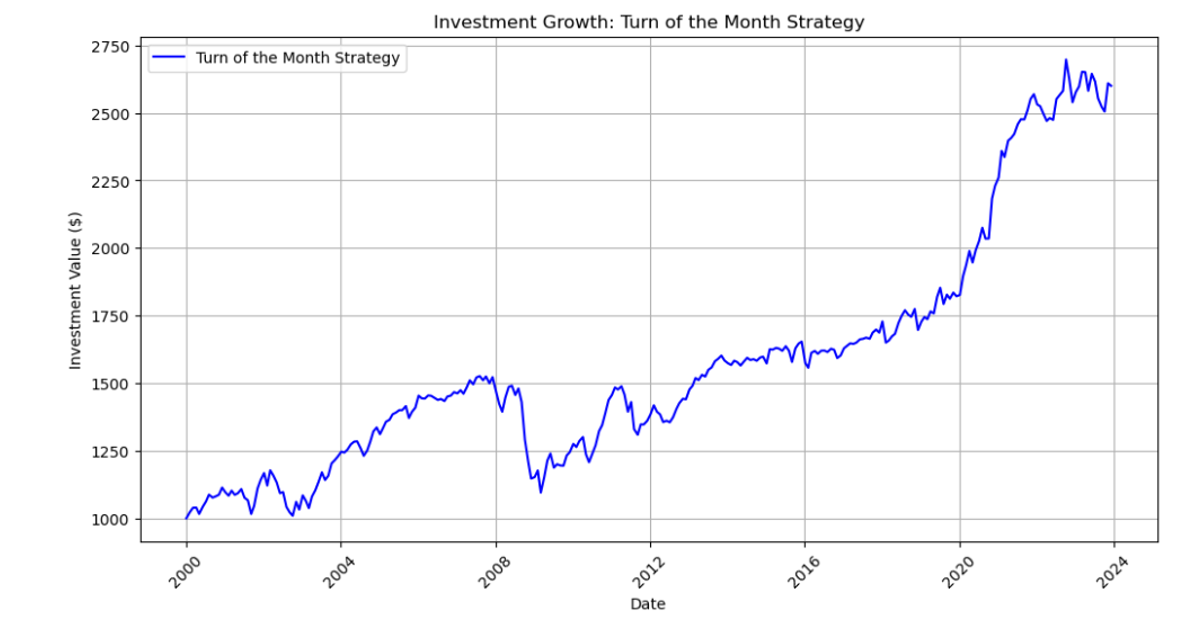

Anyway, Lakonishok and Smidt identified the effect by looking at the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) data from 1897 to 1986, which is a decent sized sample. And the effect has held up well out of sample. Here we used data from Yahoo Finance to implement a strategy where we buy SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) on the last trading day of the month, then sell at the close of the 4th trading day of the next month.

Source: Yahoo Finance (2024) Historical Price Data

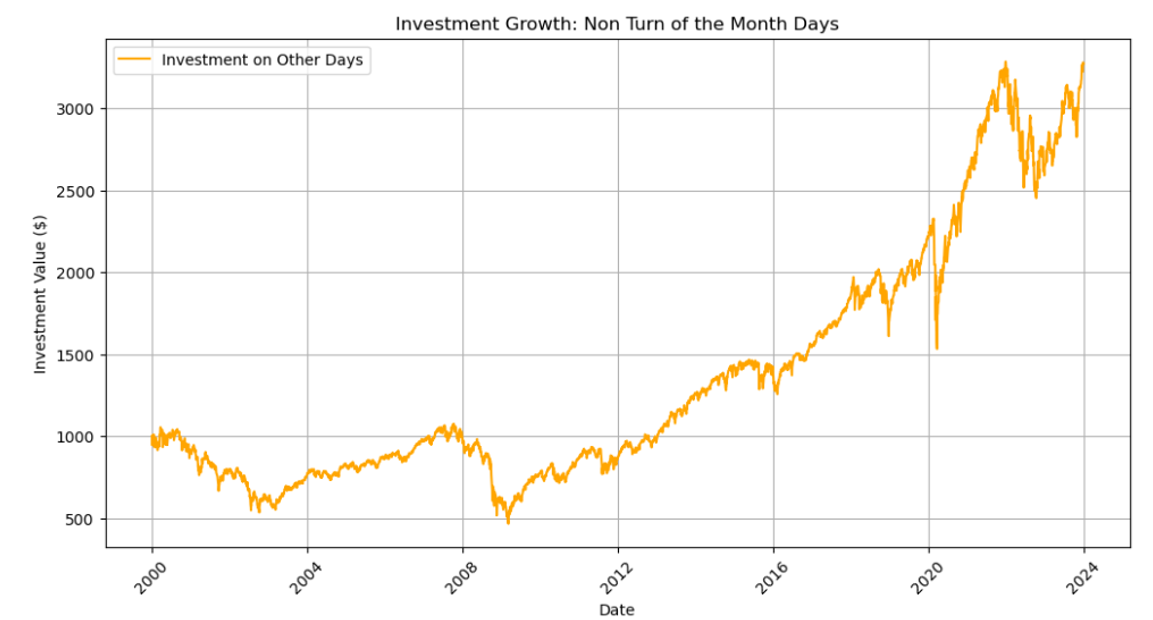

Compare this to a strategy of being long the rest of the time.

Source: Yahoo Finance (2024) Historical Price Data

Note: The SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) is an exchange traded fund which trades on the NYSE Arca under the symbol SPY. The Fund seeks to provide investment results that, before expenses, correspond generally to the price and yield performance of the S&P 500® Index. The S&P 500® Index is designed to measure the performance of the large-cap segment of the US equity market. It is float-adjusted market capitalization weighted.

The terminal value for the “Rest of Month effect” is higher by $670, but it is in the market for five times as many days. Turn of the month captures 44% of the total return (before dividends).

As an aside, we aren’t neglecting dividend here to hide anything. It is true that SPY pays dividends mid-month so these would diminish the relative performance of the turn of the month but:

- It didn’t seem to be the cleanest way to illustrate the effect. You may disagree with this.

- As we wrote about in the last entry, we don’t recommend any of the anomalies is used as a stand-alone strategy. You might want to be longer than usual over the turn of the month, but the rest of the month is also good. This is an augmentation, one of the component strategies that is used in a strategy portfolio. It is not a replacement for buy-and-hold.

The effect isn’t particularly dependent on the choice of days to enter and exit. While it is never a good idea to pick an “optimal” set of parameters based on what has happened in the past, it is important that an effect holds over a range of inputs.

If we denote the first day of the month as T (trade date), our entry was on the close of T-1 and our exit was at T+3. The table below shows the results for some different combinations.

T-1 entry T-2 T-3 T+1 exit $2,100 $1,932 $2,709 T+2 $2,268 $2,084 $2,922 T+3 $2,600 $2,389 $3,350 T+4 $2,420 $2,233 $3,117 Note: The values in the table above represent an initial investment of $1,000 in SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) since 2000.

There are plausible reasons why we think this is a real effect and not just due to chance.

First, the probability of any block of four days being so good through chance alone is very, very small. This is a valid fact, but we must always remember that there are an infinite number of theories we can test, not just “block of four days” theories. We need more than statistics without context.

And we have more.

This effect isn’t limited to the U.S. markets. It has been shown to exist in 20 markets throughout America, Europe, and Asia. It isn’t only seen in small capitalization stocks or low volume stocks. It isn’t due to extra market risk: the volatility of returns is no higher than at any other period. And it is separate from the January and Halloween effects (which we will discuss in later posts).

Finally, the turn of the month isn’t just a random group of days. Different things happen on those days. At the end of the month, institutional investors receive inflows from scheduled contributions and dividends, which they then deploy into the market. This influx of funds pushes up prices. Also, fund managers often re-balance their portfolios at the end of the month to account for withdrawals or to realign with their investment objectives. For example, a 60/40 fund will need to adjust their portfolio to stay at that allocation.

So, here we have a clearly observable effect that requires no modelling or mathematics to identify. It has worked for a long time and has been working since it was widely broadcast (equivalent to working both in and out of sample). It is robust. It works in lots of places. It has plausible reasons for its existence, and these seem likely to continue. Why not use it?

Disclaimer

HTAA, LLC serves as the investment advisor to the fund. The Fund is distributed by Northern Lights Distributors, LLC., which is not affiliated with HTAA, LLC or any of its affiliates. HTAA is not affiliated with Ultimus Fund Solutions, LLC or any of its affiliates.

Carefully consider the Fund’s investment objectives, risk factors, charges and expenses before investing. This and additional information can be found in the Fund’s prospectus, which may be obtained by visiting www.hulltacticalfunds.com. Read the prospectus carefully before investing.

Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Investments in smaller companies typically exhibit higher volatility. The Fund will invest in (and short) exchange-traded funds (ETFs). The Fund will be subject to the risks associated with such vehicles. The Fund may also invest in leveraged and inverse ETFs. Inverse and leveraged ETFs are designed to achieve their objectives for a single day only. For periods longer than a single day, leveraged or inverse ETFs will lose money when the performance of the underlying index is flat over time, and it is possible that a leveraged or inverse ETF will lose money over time even if the level of the underlying index rises or, in the case of an inverse ETF, falls In addition, shareholders indirectly bear fees and expenses charged by the underlying ETFs, as well as the Fund’s direct fees and expenses. The Fund may invest in derivatives, including futures contracts, which are often more volatile than other investments and may magnify the Fund’s gains or losses.

The Fund is an actively managed ETF and, thus, does not seek to replicate the performance of a specified passive index of securities.

The Fund may take short positions. The loss on a short sale is theoretically unlimited. Short sales involve leverage because the Fund borrows securities and then sells them, effectively leveraging its assets. The use of leverage may magnify gains or losses for the Fund.

There is no guarantee that any investment strategy will produce positive results. There is no guarantee that distributions will be made.

LEAVE A COMMENT