-

- February 13, 2025

- 0

Inflation & Volatility

Inflation is probably the economic phenomenon that is most emotive to most people. Unemployment only directly affects a few people, but everyone sees prices go up. Further, the effects continue to be felt. Even when inflation drops to normal levels, prices don’t go down again. There are plenty of people who still think inflation is high even though it is back to a normal level.

But financial economists don’t seem nearly as interested. In particular, there is very little published research on the link between inflation and volatility. So, I thought it would be worth a quick look. I’m not trying to predict anything here. I just want to see if there is a link. If there is no clear pattern we don’t need to go any further. Observation should always come before prediction.

I used Consumer Price Index (CPI) data from the St. Louis Fed and S&P 500 Index (SPX) data from Bloomberg.

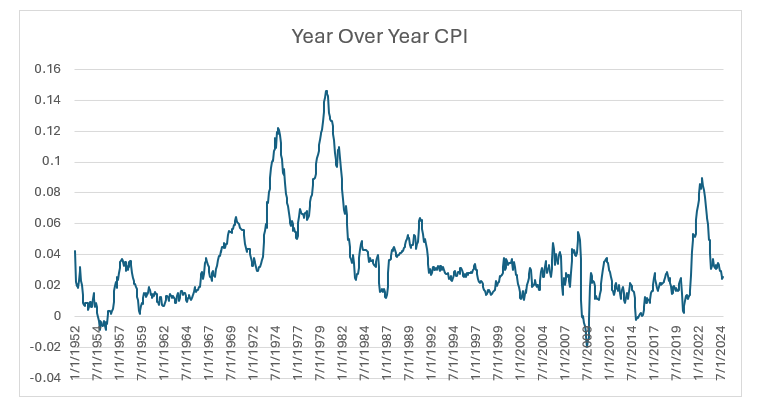

Since 1952, the percentage change in CPI over the past year has been:

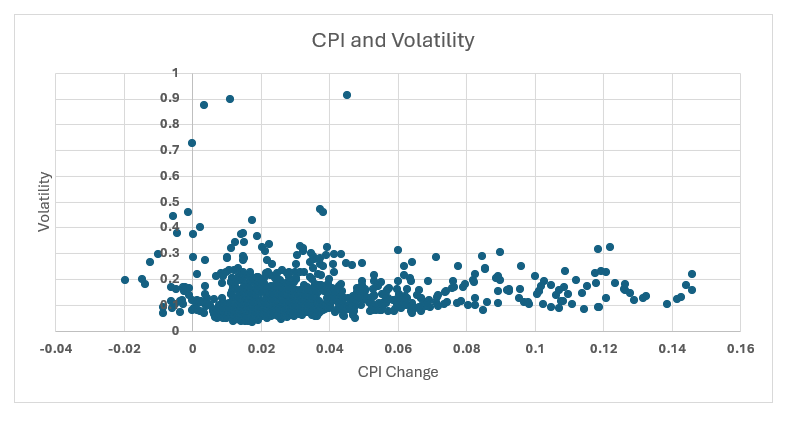

And the relationship between CPI and one-month realized volatility is:

There is a slightly positive correlation of 5.2%.

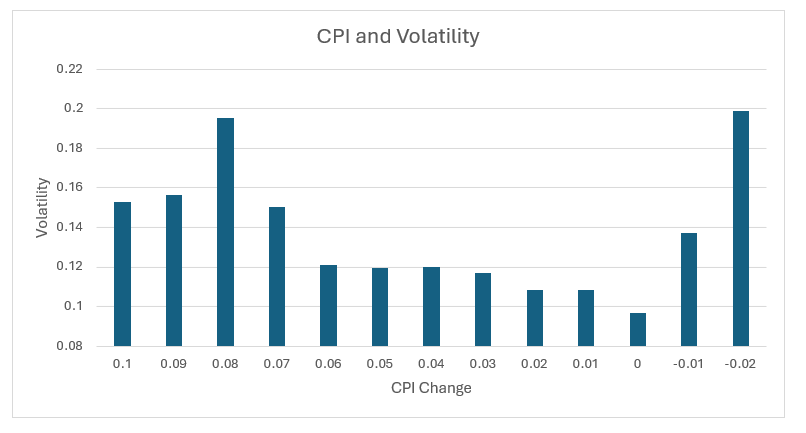

Expressing this relationship as a decile sort still gives something of a mess. It also isn’t the way we think of CPI. We would be more inclined to say, “inflation is 10%” than “inflation is in the 95th percentile”. So here we bucket volatility by CPI levels. So, for example, when inflation is between 9% and 10%, the average volatility is 15.6%.

To me, this chart has two interesting features. First, when inflation is high, volatility is higher than average (13.6%). And a deflationary environment is also associated with high volatility.

Where does this leave us? The last CPI year-over-year change was 3.0% (as of February 2025), which corresponds to an uninteresting, slightly below average volatility. Where things could be interesting is if the new administration go through with their tariff threats/promises. Even ignoring the clearly hyperbolic promise of taxing Mexican car imports at 2000%, the proposed tariffs would be inflationary. The Budget Lab at Yale has estimated that the effect of tariffs would initially increase consumer prices by over 5%. Taken in isolation this would see a significant jump in volatility.

Of course, tariffs won’t be the only factor influencing the markets, so we can’t be very confident in this prediction. In the 90’s there was a lot of chatter about volatility being a new asset class. It seems like it behaves like most other assets in at least one regard. Just like the price of gas, higher inflation causes volatility to go up.

Disclaimer

This document does not constitute advice or a recommendation or offer to sell or a solicitation to deal in any security or financial product. It is provided for information purposes only and on the understanding that the recipient has sufficient knowledge and experience to be able to understand and make their own evaluation of the proposals and services described herein, any risks associated therewith and any related legal, tax, accounting, or other material considerations. To the extent that the reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to their specific portfolio or situation, prospective investors are encouraged to contact HTAA or consult with the professional advisor of their choosing.

Except where otherwise indicated, the information contained in this article is based on matters as they exist as of the date of preparation of such material and not as of the date of distribution of any future date. Recipients should not rely on this material in making any future investment decision.

The S&P 500® Index is designed to measure the performance of the large-cap segment of the US equity market. It is float-adjusted market capitalization weighted.

LEAVE A COMMENT